Chapter 17 – Pagami Fire

Mr. Gubbe was a very nice man. He lived with his wife and daughter in a little house behind the DNR office on the Old Scenic Highway, just a few miles down the road from where I grew up. He was a forester with the Minnesota DNR, and along with his other duties, he would come to our rural three-room elementary school every Arbor Day and give a little talk on identifying trees, or the importance of the forest in our environment or what Smokey the Bear’s message should mean to us. At the end of each program, he would hand out a single red pine - wrapped in plastic – for us to plant in our yards when we got home. One year he brought a bucket of pine trees for all the kids in the school - numbering about 50 - to plant along the edge of the school property. That stand is still there today, 60 years later.

He was also in charge of fire suppression in the area. Every spring there would be numerous grass and brush fires that would break out. Someone would call him, and he would load several shovels and rakes and axes, along with half a dozen galvanized water tanks with hand sprayers that could be worn on the back into the back of his state-owned pickup. His wife would start the call tree that notified all the families near where a fire might have broken out and ask for volunteers. In most cases this first line of defense would control what began as a spot fire and keep it from turning into a large, uncontrolled burn that required larger equipment and manpower.

My dad would get the call two to three times a spring. If he wasn’t at his shift for U.S. Steel, he would throw his own tools into the back of our truck and meet up at a rally point. A few hours later he would return, red-faced and full of soot and declare another success story. Occasionally a couple of men would be left at the burn to put out any flare-ups that might occur.

The spring I was twelve years old I began to accompany my dad to these fires if they weren’t too big. Most times I would be assigned a #2 shovel or rake to beat out the small flames along the back edges of the burn area. On occasion I would get to wear one of the heavy water packs and douse the duff along the forest floor where hot spots were occurring. At the end of fire season, anyone who had spent time as a temporary “employee” would be paid for their work. I have no idea what the hourly rate was, but in July of my first year of fighting fire I remember getting an official check from the State of Minnesota for $8.

Fast forward to August of 2011. What started as a lightning strike near Pagami Creek at the end of the Fernberg Road, roared into an inferno several days later that consumed over 92,000 acres of forest. From the beginning, because of the remoteness of the fire, only professionals were allowed in an attempt to control the blaze. Several factors, including a dry summer, brisk winds and a lot of forest floor fuel from a massive blowdown in 1999, led to it quickly spreading into a large, living entity. The USFS, attempting to lessen the fuel on the forest floor, scheduled a controlled burn that increased the intensity because of a rapid shift in weather conditions. Residing on the edge of the affected area, we had daily reminders with smoke plumes clearly visible and a smokey haze that hung in the air that burned the eyes and lungs. Flames reaching skyward could be seen from miles away. Campers and Forest Service personnel were at great risk. If you ever have a chance to see “Pagami Fire” by WildlandFire LLC on You-Tube, take a look. It is an intensive story about what the conditions were like near the center of the fire.

My firefighting days had long been over. Many residents in the area were instrumental in supporting roles of providing backcountry equipment, meals, communications and accommodations as tired firefighters were rotated out for brief periods of sleep and rest. Hot Shot crews from all over North America were brought in. Firefighting aircraft from both the U.S. and Canada were used. Smoke was photographed from satellites high above the inferno.

It was a major news story for many days. Nick Wognum of the Ely Echo got in touch with me and asked if I would represent them on a USFS media tour for outlets to see some of the action firsthand. I jumped at the chance and was soon gathered with correspondents from newspapers and television stations from Duluth to Minneapolis, to Chicago, to St. Louis and beyond. I was along on two trips into the burned area. Though we weren’t going into any of the intense areas, we were outfitted with fire retardant clothing and a fire survival tent and had to spend time learning how to use them in case we were surprised by unforeseen conditions.

The first trip brought us near Silver Lake and were introduced to a Hot Shot Crew from Arizona. They were tasked with “mop-up” behind the main fire. Their job was to tamp down hot spots and to combat flareups that might occur. Though the fire was primarily suppressed, the thick, acrid smoke hung heavy in the air and the heat from the freshly burned earth caused the bottoms of my boots to become uncomfortably hot. Face masks against the smoke were worn by many. We spent an afternoon with these firefighters and gained additional respect for the work they do under very difficult conditions.

Our second foray was a canoe trip starting at Kawishiwi Lodge on Lake One and paddling into Lake Four. Several news outlets were involved, and I had Dan Kraker of MPR News with me in my canoe. This trip was to inspect the damage the fire created on the mainland and islands along this chain of lakes. Hot spots still smoked and would continue until the snow arrived in November. Interesting was how the fire hopscotched from island to island and lake point to point. Some were burned deep into the soil, where others were left unscathed. The forest that once was there was now changed for a generation.

Move ahead one more time to 2020. Going into the burn area, one could see immense recovery and regeneration. Black scars were almost gone. The undergrowth was thick and diverse. Jackpines formed walls almost impenetrable. Campsites were slowly returning, and recreational usage reached all-time highs. I became intimately involved one more time.

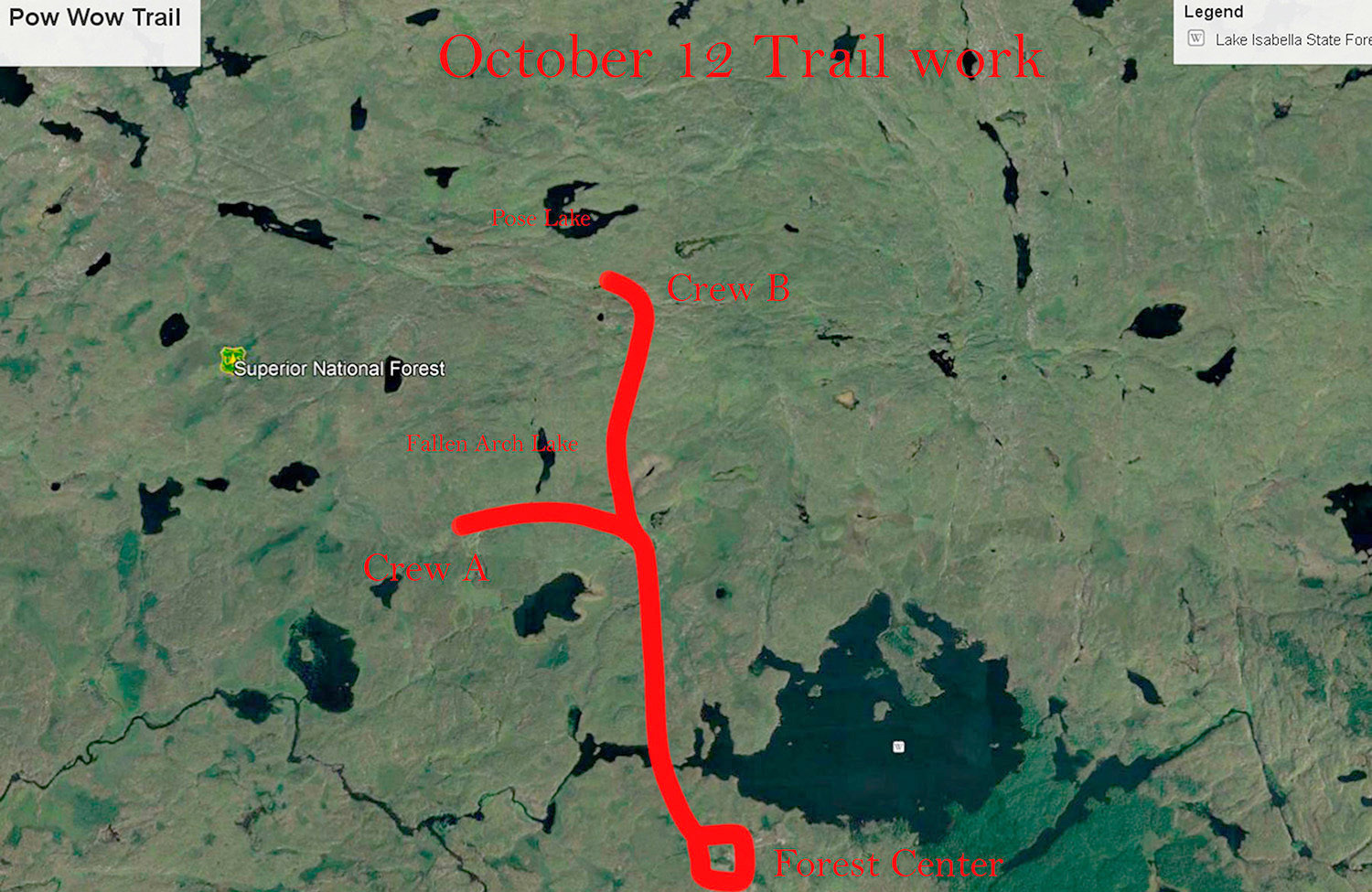

Much of the area that burned included a rich history of the last 150 years that included fire towers, logging roads and camps, hiking trails, CCC Camps, NIRA camps and cabins and resorts that had once existed. Volunteers became involved and, in cooperation with the USFS worked to restore and maintain some of the old trails. The Powwow Trail is a case in point. Established as a trail system in the late 70’s, it was in the middle of the Pagami Fire. Completely eradicated, an organization called Boundary Waters Advisory Committee – BWAC proposed to volunteer clearing the old trail and maintaining it. Over several years and much effort, that has been accomplished. Multiple trips over several years removed blowdowns – by hand – and cleared underbrush and the incessant jackpine renewal along the route. The initial work done; they now have moved on towards maintaining that trail and helping to maintain others.

Another group – Boundary Waters Heritage Trails is newly formed and as part of their charge, intends to identify and educate the historical aspects of the area dating from early history to recent times. This group is only a few months old and is getting its feet under itself. Early work includes researching maps, archival records, interviews and survey notes to establish what was present from the late 1800’s until the early 1980’s. I have worked with both these groups and find them valuable and immensely interesting.

Forest fires are frightening. To be in the path of one or even close while it is burning must be a terrifying experience. The aftermath is seen for hundreds of years. And yet, they have historically burned all portions of the forest about every 300 years. The environment endures. The mature red pines and white pines that survive today were born of a fire centuries ago. Humans have been only a small part of this story. In between fires we build structures, roads, communities and harvest the bounty that the wilderness provides. We lament the changes that a fire brings to our life – the forest skyline, a favorite stand of trees, a route once traveled and maybe even a shelter once enjoyed. And yet, our few decades on earth are no match for the centuries and millennia that the forest has been here and will be here after we leave.