For the first time in four years — after the COVID-19 pandemic and then a $9.3 million reconstruction project — public tours of the Soudan Underground Mine in northeast Minnesota are poised to start up again on Memorial Day weekend.

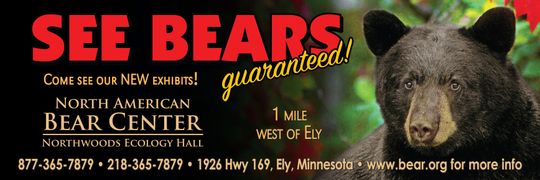

For decades, visitors to the Lake Vermilion-Soudan Underground Mine State Park between Tower and Ely have been able to descend more than 2,300 feet underground into the state’s oldest iron mine.

The mine opened in 1882, initially as a series of open pit mines. Later tunnels plunged deep underground to target a rich ore body used to forge steel vital to the nation’s rapid industrial development.

The mine closed in 1962 and became a state park three years later. About 35,000 visitors from around the world travel deep underground every year using the facility’s vintage equipment to learn about the mine and its history.

“Most mines that close don’t continue operation because you have to use pumps to keep the mine dry and somebody has to pay for that,” explained Interpretive Supervisor Sarah Guy-Levar.

“And most active mines certainly don’t offer tours because if you have people in your cages, you are not hauling ore out of the ground, so you’re not making money. So Soudan is an incredibly unique experience.”

But to continue offering that experience, the aging mine required significant maintenance. Eighty-fiveyear- old steel and a concrete lining in the mine shaft was degrading, and a long section needed to be replaced.

Over two years, contractors removed 70 dump truckloads of debris and thousands of square feet of concrete. They lowered 2,000-pound steel beams and tons of concrete to rebuild the shaft lining and steel infrastructure that supports the rail and rollers on the cages that move visitors up and down the mine shaft.

“And now we have a very, very strong steel structure. We don’t have to worry about anything caving in, on to the cages,” Guy-Levar said. “And it is a smooth ride right now!” Into the mine

While public tours resume on May 25, 2024, for the past few weeks school groups have been visiting the mine, including a 5th grade class from Hibbing that toured the site last week.

Guy-Levar herded about a dozen kids, and several adults, into a disconcertingly small steel cage for the descent down the mine shaft. It’s only 5 feet across, 6 and a half feet deep. The passengers squashed in like sardines.

Tour guide Karel Winkelaar suggested they should enjoy the ride. “If we were mining in those early years, we put as many as 18 fullgrown men in that cage with lunch pails and hand tools for the day. So we’re going to be riding in luxury.”

The cage zoomed down through the rock, rattling as it plummeted at a speed of more than 10 mph, dropping one thousand feet per minute, to the 27th and deepest, level of the mine.

Then the students climbed on a train to ride about a mile to the last area that was mined. Winkelaar led them up a steep spiral staircase, into a large cavern, dug out of the rock.

“Right now we are in what we call the stope,” he explained. “This was the ore body that we’re in right now.”

Workers mined all the ore from overhead, and dumped it into deep holes in the floor to get hauled to the surface.

Mineworkers called Soudan the Cadillac of mines, because compared to other operations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, working conditions were relatively good. It was dry and had good air ventilation.

Winkelaar shut off the lights in the mine. It’s so dark students couldn’t see their hands. He lit a small candle and stuck it in his hard hat, just as miners would have done a century ago, to see and work with both their hands free.

Miners had to buy those candles themselves. And they only got paid for the ore they hauled to the surface. They worked 12-hour days, six days a week.

Winkelaar asked the students to put themselves in the shoes of the miners, many of whom were recent immigrants from eastern Europe.

“The company is going to be taking advantage of you. You guys are immigrants. We’re gonna give you the jobs that nobody else wants to do.”

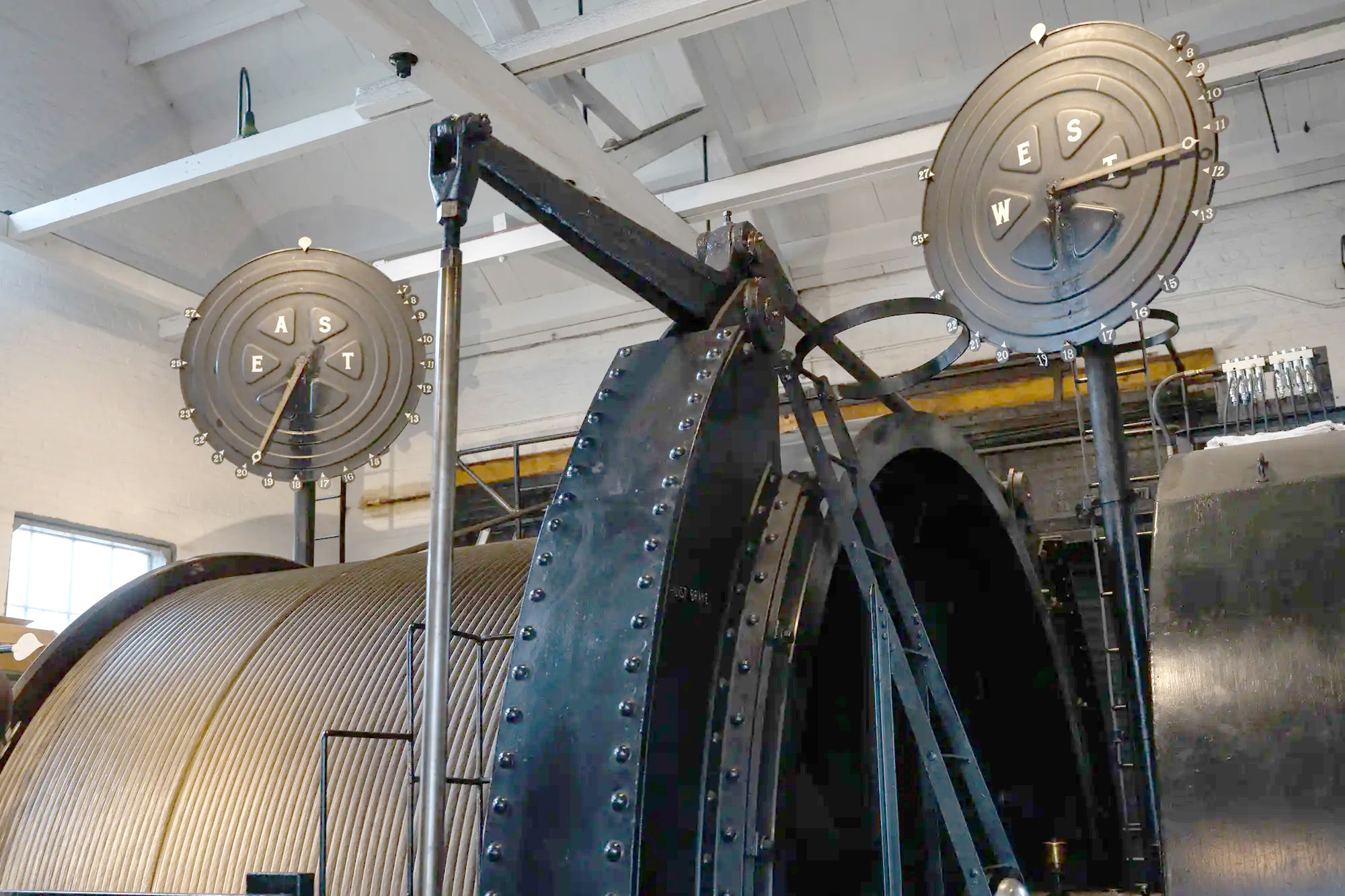

‘Custodians of history’ Back on the surface after the hour-and-a-half long tour, students watched 3,000-foot long steel cables unspool from a massive drum to lower the cages down the shaft. Huge dials show where the cages are in the mine shaft.

This Allis-Chalmers electric hoist system turns 100 years old this summer.

“We’re custodians of history,” said Jesse Gornick, lead maintenance and hoist operator at the park.

Gornick and his colleague Steve Yapel keep the vintage equipment operating smoothly. Lots of grease, they joke, is critical. Both their grandfathers and great-grandfathers worked at the Soudan mine.

They take that history seriously, especially the critical role Minnesota played in supplying the ore that made the steel that was used to fight in World War I and II. “Expressing the knowledge and importance of mining to others is important,” said Gornick. “And keeping it alive for future generations to understand why it’s important.”

They also share a deep sense of responsibility to keep visitors safe.

“It’s very satisfying, knowing that a lot of the equipment’s that’s used today was used then, and they worked on the same things we’re still working on,” said Yapel.

This is the 59th summer of tours at the Soudan mine. Guy-Levar expects pent up demand.

“Please make a reservation,” she said. “Don’t be disappointed because there have been so many people waiting to take a tour.”

If you go

Tours lasting 90 minutes are offered from late May through the third week of October. The temperature in the mine is a constant 51 degrees year-round. Wear a jacket and sturdy boots or shoes.

Tours cost $15 for adults, $10 for children 5-12, and are free for children under 5. Reservations are recommended.

No purses, backpacks, or strollers are allowed underground. The three-minute cage ride down to the mine is in a dimly lit, closed, confined space.

.jpg)